Soft Goods Design

Some 15 years ago, after his university degree in Product Design, Tristan transitioned into full time work in the Gold Coast’s booming surf industry. This is a raw and true chronicle of his experiences.

“During uni I landed my dream job working for a surf label as a designer. I started with Cult Industries, a now lessor known brand, but at the time a burgeoning super star like the other big three, Billabong, Quiksilver and Rip Curl. Season after season I would develop product, with no understanding of its forward-connection; its footprint. I very quickly became bitter with my practice. I almost immediately sensed the reality of what we were doing, which was consumerism in action, on a seasonal scale (300 pieces, 3 times a year) and without any ecological consideration. I knew something was wrong, yet I had no sense of what was an alternative way. I quit.

As most twenty-somethings do, in order to ‘find myself’, I backpacked around the world for 3 months. My eyes were wide open as I traversed cultures and spaces on all four corners of the globe. Yet I had still not found that ‘utopian’ solution, so I returned to Cult only to last another 8 months before my morals gnawed and again, I quit, and I traveled.

At this point it would be easy to suggest I was running away from the problems my mind had identified, but I would rather acknowledge that at the young age I was, around 23, it is imperative to go, to see, to be exposed face to face with what the mind suggests are problems in our world. The crisis is however, that humans have no name for the most critical problems we face, such as unsettlement, displacement, climate change, war, poverty, perpetual motion economies, destruction of natural resources and so on. They are not seen as one entity and therefore extremely difficult to identify and confront. The ‘baggage’ taken when travelling as a young person is not full of a solidified notion of the unsustainable, if it were, we can only imagine how much more effective young minds with eyes wide open traversing the world may be!

Whilst living in Japan for nine months I learned to live lightly. Actively, but with little option, practising a tiny home lifestyle, in a room no bigger than a kitchen. My girlfriend and I had everything we needed. Spending my time freelance designing for clients in Australia and teaching English in cafes on the side, neither challenged my thirst for higher knowledge. I spent time reading books and watching documentaries on the sciences, archaeology, history, design and philosophy. It was akin to adding fuel to an already inquisitive flame.

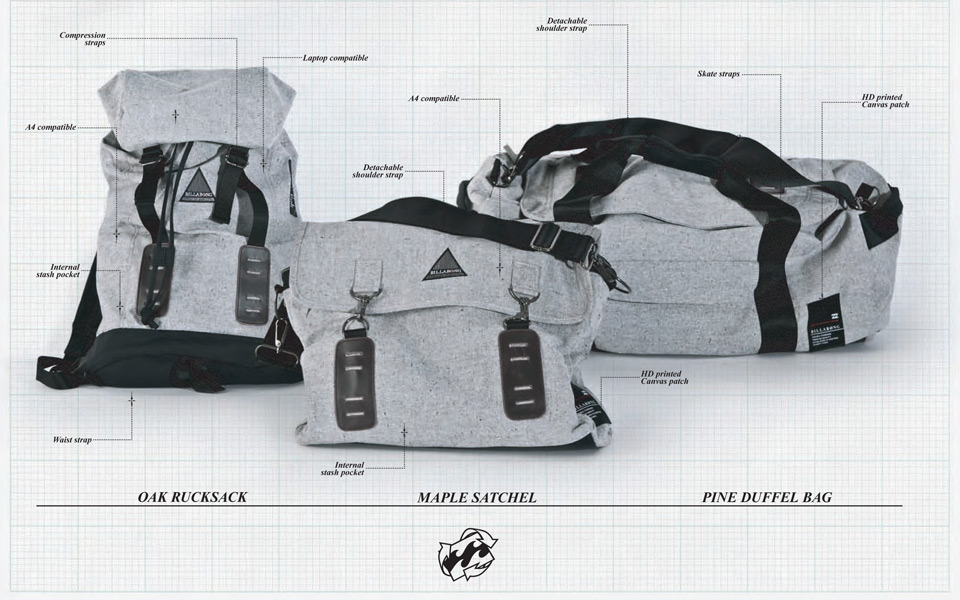

In the ninth month living in Japan, Billabong – the biggest surf company in the world made contact. They invited me to come home to the Gold Coast and head up the accessories design department as Design Manager. This was a massive leap in a career path, a design management position with an inviting package and Billabong placing faith in me that I could rise to the challenge and do the job.

By this point I was conscious of what I had been through in the previous years with Cult Industries. I was conscious I was looking down the barrel of another model of high volume consumerist on-trend product, yet I justified a difference; the position description talked about sustainability, eco-product and technical advancement in its key performance indicators. I took the job.

The first six months was filled with wrapping my head around the core tasks at hand of running a team of 10 designers and a global product program requiring travel to USA, Europe, UK, back to Japan, China, HK and Australia. The next six months I was able to ‘practice’ these core tasks autonomously and start to identify ways I could live up to the key performance indicators that lured me in.

For two years I spent many a late night at my office desk scouring over supplier capabilities and researching how we could make our product more ‘eco’. Unfortunately, just as I was deep into implementing several solid eco initiatives, the global financial crisis hit. Syncing with this, cotton became scarce due to climate changes around the world (which in turn increased the demand and price on polyester) and Billabong found itself in a fight for survival amongst unprecedented pressures. ‘Eco’, is seen as a marketable luxury rather than an underpinning norm by companies in these times of crisis. I was left in a position of fighting to keep my department afloat. Whilst delivering redundancy packages to half my team, and China’s supplier prices skyrocketing, the last thing that anyone wanted to do is utilise a certain eco process that would decrease our margin by 3%.

Within such an uptight, high-pressure environment embroiled in delivering sales figures as the only way to survive, my embedded inertia resurfaced. Sure, I could weather the storm and continue with a process of increasing eco-product on the other side, but now I began to ask why? Why does ‘Little Johnny’ need the next best backpack we design for him, no matter how much I reduce its footprint? The last one works just fine. I understood I was merely exploiting the social construction ‘Little Johnny’ was inducted into, the very construction I was beginning to see as filled with flaws. The consumers’ desire for the product I was bringing into existence was for the most part based purely on the identification of an aesthetic re-branding that suited the on-trend palette of the day. This is the precise point in which I grasped the notion that what I was designing had a life of its own, and would go on designing. I was accountable for the perpetual momentum of these products well beyond leaving the factory. I was creating desire, Design is not separated from desire (signs link the two) so, we have responsibility for what we bring into the world semiotically.

I was bitter, and before I could even make a decision for myself to quit like I had at the previous company, the decision was made for me. The economic crisis forced Billabong’s board to undertake redundancy on middle management across the entire company. Design was the first dept to filter. I was reluctantly offered a redundancy package via my emotionally exhausted boss. I took it. The very next day Quiksilver (the worlds ‘other’ largest surf company) called and invited me to discuss heading up their global luggage design out of Torquay in Victoria. This time though, I declined.

My time spent with Billabong was rife with excuses; I would constantly take a public moral stance that I am only interested in the technical luggage and backpack ranges because they serve a function of a higher order than say a t-shirt, but the reality was that many of the products I was responsible for were simply re-configuring existing innovations (pockets, zips, fabrics, openings) seasonally into different aesthetic patterns. I was sustaining high volume throwaway culture consumerism – the unsustainable.

I am forever appreciative of Billabong for giving me the space to research new design solutions with better processes that will cause less harm to the environment. This was a focus for me. Simple things, such as eliminating cheap plastic water bottles, advocating for the eradication of PVC in backpacks, using raw hemp canvas, and injecting more timeless forms and graphic identities released from the mercy of trend redundancies, were a few in-roads. In the end, my mission was to design and develop high quality functional products that paved the way for less needless ‘stuff’ in a saturated marketplace. I thank Billabong for allowing me to contribute to inspiring solutions that have the potential to transform the company into a more environmentally conscious brand.

All this is not to say brands accommodating trends should not exist, but the agency that drives their existence needs dramatic re-configuring. Patagonia seem to have worked towards this end. Their website states: “The wild world we love is fast disappearing. At Patagonia, we think that business can inspire solutions to the environmental crisis. This means that what we make and how we make it must cause the least harm to the environment”. Through their ‘footprint chronicles’ each product’s life cycle is made visible. They take remarkable steps to minimise impact and discourage short-term product redundancies.

After Billabong, I spent some years freelancing for different brands. After all, I was passionate about good functional soft good product like backpacks and wallets and I was keen to see my skills transfer to small local brands with strong ethical positions. For example I worked with Ellaspede to help start up their brand. Ellaspede is made up of a dedicated team of industrial designers. Owned and operated by Steve Barry and Leo Yip, Ellaspede is a hub for motorcycle culture and creativity. Ellaspede also design and develop a range of products. A long term project began in 2011 to extend Ellaspedes brand ethics of high quality bespoke engineering in their motorcycles to an accessories and apparel range with the same ethos. Small qty, timeless, crafted and limited runs of product with sustainable material and construction in mind. Locally sourced vegetable tanned leathers, local printers, embroiderers and craftsman were some of the ‘ground-up’ processes I developed with the team.

I still continue today to selectively draw on my soft good product design skills for projects that fit with the Relative Creative position. After all, everyone needs a place to store some things and hoist over their shoulder.”